When I was a teenager, my mother painted leafless trees on the walls of her 1920s farmhouse, and to this day calls them “naked trees.”

But leafless, naked or dead, her fascination with these trees seemed odd to me. I didn’t dislike bare trees, but it struck me as odd to celebrate a lack of life. Wasn’t life the important thing? Weren’t green, living trees better?

Of course, as these things usually go, I am learning more and more how much of my mother I am. I am now convinced that dead trees are not only wonderful themselves, but are selfless martyr-architects of the natural world.

All trees die. A dead tree in a yard doesn’t often mean much to people. It’s considered an eyesore, or a hazard in case bad weather topples the thing into your house. So, most yards, avenues, and city parks are curated to keep the presence of these dead trees to a minimum.

When a tree (or even a limb) dies, it gets the saw, and it disappears, clipped from public consciousness forever. The exceptions are relegated to empty lots, foreclosed homes, and “unscrupulous” landowners.

National Parks don’t have the level of meddling that our yards do. Not that it matters. An HOA with the Pentagon’s budget would be ill-equipped to remove all the dead trees from Yellowstone.

And still, the idea that living trees are better, more beautiful, more useful, and more important in nature is a weird suburban dogma we’ve brought to our National Parks.

It makes sense emotionally. Big tree-die-offs are spooky. Anyone reading this who has been to a National Park after a forest fire or insect outbreak knows what I’m talking about.

It’s overwhelming. I have driven through miles of dead trees standing like poles, austere and emaciated, black and peeling, scattered across formerly green wonderlands, and felt a sense of tragedy. We instinctively feel connected to trees, especially old, big, or endangered trees.

At Glacier National Park, one interpreter gave us succinct advice on how to identify the rare high-elevation whitebark pine tree: you can tell them apart because they are all dead.

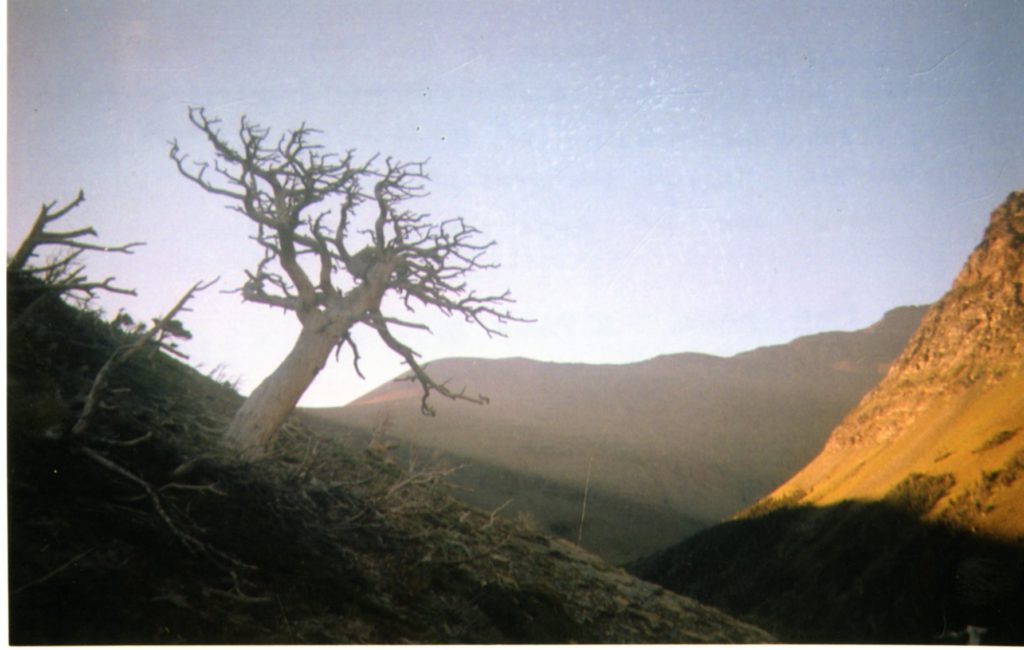

Which, after he had been using bird puppets to explain the ecology of the Northern Rockies, was a bummer, to say the least. The next day of that trip Bret, Ned, and I backpacked up and over Scenic Point toward East Glacier. There were many dead trees on our path, and I took a photo of one, which is probably a Whitebark.

It’s my favorite photo from the trip.

The tree itself is beautiful: Gnarled bony limbs, defiantly grown out of solid rock, frozen in place for time that errs toward eternity. It is a naked tree, not just for lack of needles but because it is exposed. It stands, arms spread skyward, year over year, subject to snow, ice, rain, wind, tourists, and termites without any qualms or complaints, perched 7,000 feet up in what is called Montana since before it was called Montana.

It was a stirring moment that I love to reflect on.

“I hate seeing dead trees. I didn’t drive an hour to hike through dead trees.”

OK, so maybe the feeling isn’t mutual. My friend Sarah, as shown above, is not a fan of dead trees. In her perspective, they’re ugly. More than that, though, she wants to spend time in living spaces. “Some of these forests are really unhealthy. Dead trees all over the place,” she says. Her opinion is the majoritarian position. People don’t hike in the burned areas of National Parks, really. When fires erupted near King’s Canyon National Park in 2021, people felt afraid, not for tourists, but for the ancient sequoias of the park. Even Bret asked me to route our 100-mile backpacking trip to avoid recently burned areas in the wilderness.

People are unsettled by dead trees, which I understand. But is death unhealthy?

I’m being sincere! I think most people would be hard-pressed to find a positive that comes from 200,000-acre fires obliterating whole forests.

But are there?

Like most things, their value is obscured by distance. Get up and personal in one of these “snag forests” and see for yourself. Walking through, not driving past, these forests is captivating.

For one, they are not really dead. These snag forests are so alive!

Yes, the tall spires of dead trees remain, but now as Ent-ish shepherds for thousands of saplings carpeting the forest floor. Flowers abound, especially the apt-named fireweed, and any pollen-seeking thing is too: Bumblebees, hummingbirds, butterflies.

Ground squirrels weave through the fallen trees and hawks chase after them. Moose gorge on young alders. Bugs of all shapes and sizes go wild for the new real estate, unchallenged by the sappy immune systems of living lodgepoles, and feed all sorts of animals in the big wild chain.

My mom and dad did see Yellowstone just after the 1988 fires, which were some of the largest in the park’s written history. Drive there now, and what do you see?

Meadows have reclaimed thousands of acres, which bison and elk continue to benefit from. Blackened, hollowed trees provide cavities for mountain bluebirds and great grey owls. Fallen logs shade streams, keeping water temperatures low for cold-water fish like cutthroat trout. It’s a pheonix-like paradise.

Dead trees become food and shelter; help filter and slow spring runoff; and make for delightful photographs. What’s not to love?

Respect the dead!

Well written, Paul! If we didn’t have the dead trees, the forests wouldn’t regenerate…you explained that in a beautiful tribute to the dead trees!

In the Wikipedia commons, there is an amazing photo – the attribution is: By Brocken Inaglory – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4286917. It is stunningly beautiful, captivating, and the sentinel trees make the photo. I’ll email it.

Every day on the way to work, I pass by a lovely dead tree on the west side of I-15. It always has a bird of prey sitting at the top – often a bald eagle. While I love living trees too, it is easier to “twitch” when the leaves aren’t hiding the birds!

Nice article. I never understood the beauty of the forest’s cycles of birth and decay until I had the opportunity to collect and photograph myxomycetes and fungi in the New Mexico mountains with a scientist friend. In the nature of the forest nothing ever really dies, it just changes form in an enchanting regenerative cycle. And in the process we get to enjoy the beauty of a naked tree.