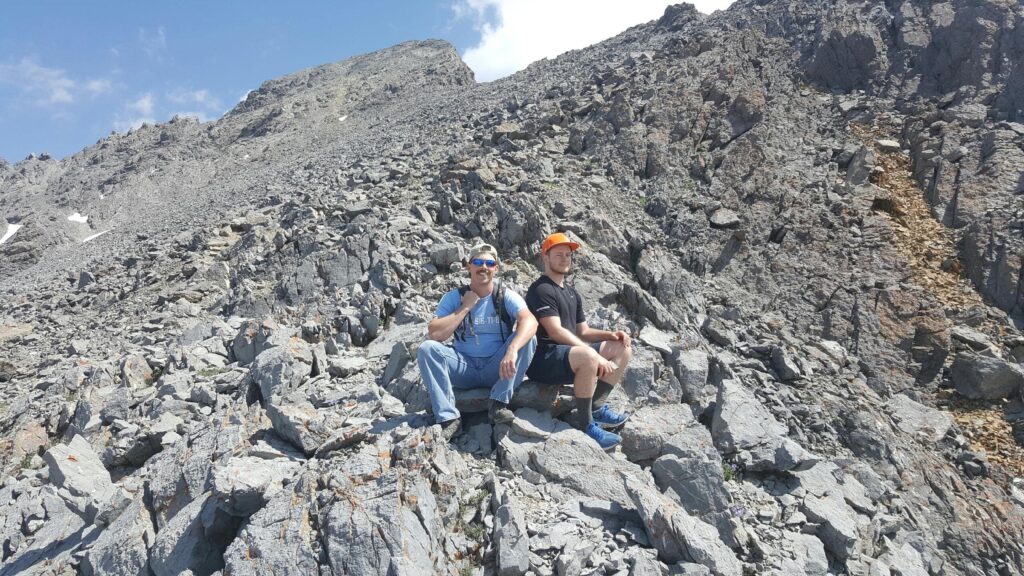

Ned and I on top of Idaho’s highest peak in 2017.

Making Friends in Public

Imagine a world where strangers greet you when you see them, where you can trust your neighbors to help you in a bind, and where everyone feels part of something bigger.

You’d expect that from a Frank Capra movie, but it’s downright naive to expect that anywhere in 2020.

It does exist: in our public lands.

On this American holiday of Thanksgiving, I can’t help but smile and think of the warmth, generosity, and friendliness of the folks-out-of-doors.

And how strangers saved our necks on Mount Borah.

Along the Trail

In 2017, my friend Ned and I decided to climb Idaho’s Borah peak. We were new to the high country, and online guides only provide so much help when confronted with the Pollock-esque landscape of stone, snow, and sky. Trails disappear, and confidence erodes.

Our trail-mates who guided us up the mountain.

But like most trips, we were not alone. A pair of young men—total strangers—walked with us, offering bug spray and direction, of which we had neither. I can’t recall their names, and even their appearances would be hazy without this photo:

Slowly but surely, our group navigated the talus maze. In short order, we made it to chicken-out-ridge, the ice bridge, and the final push to the peak.

Reaching the peak was a rush. We never would have come close without the kindness of strangers.

This kind of immediate solidarity isn’t the exception to adventuring, it’s the rule.

A Land without Walls

Why are strangers so willing to connect and support one another in the wilderness?

In Glacier, we shared tea with exhausted Texans. In Capitol Reef, I was offered space with fellow campers when all the sites were occupied. Near Bryce Canyon, a local desert rat lock-picked my truck when I had accidentally locked myself out at midnight. A cowboy offered Bret and I total support in the depths of the Selway Wilderness, mere minutes after meeting him.

Jumping a dead battery, getting food and drink, sharing directions, or just trading stories are all commonplace in public lands.

But nature is a distinct world from human society. Other humans are a rare sight still in some of our wild places. We are all lucky just to be there.

After one mile or one-thousand, seeing another person out in the wild still makes me happy.

Every time you see someone in nature, it is a gift. They believe in what you believe—that our lives are best lived wild, that nature demands our respect, that we owe something intrinsically to those strangers along our trail.

Though how we reach those aims differs, I doubt that anyone on any trail in this world would disagree with that higher purpose.

Maybe some readers will disagree, separated by screens and walls and wires, but find me one person who doesn’t believe in the value of solidarity at 10,000 feet. It can’t be done.

A Wilderness of One

Why do we forgo the love of one another that comes so easily in the wild to those in our own cities?

Wilderness, for most of time, has been the rule, and society the exception. The first Thanksgiving was survived, much less celebrated, and only because of the kindness of Tisquantum, a Patuxet tribal member who decided to teach colonizers how to grow corn and catch eels.

But this is not 1621. The bewildering pace of “progress” in the last 499 years has created a new world. As a result, our lives are marked more by excess than want.

Then why do we forgo the love of one another that comes so easily in the wild to those in our own cities?

Recently, I was evicted from my apartment. I had 24 hours to pack up and leave. All my belongings have been in my car since.

When you’re backpacking, carrying everything you own, the act of packing carries almost religious significance. Everything you own, all your means of survival, are crammed tight within a forty liter bag.

But in a city, it feels so much more dangerous. The risk of theft is constant. No corn grows in the avenues, no eels swim in the rivers, and even clean air is hard to come by.

In a city of hundreds of thousands, I was a wilderness of one.

In the age of excess, it is no longer us against the wilderness. Today the mantra is, “Life is what you make of it,” which must also mean. “and if you fail no one is obligated to help you.”

Saint Francis’ service to the unfortunate in the forests of old sounds absurd today. We see “The Unfortunate” as simply “the Undeserving.”

But compassion remains possible.

Weathering the Storm

Ned and I spent too long on the peak. An afternoon storm was brewing, and as we scuttled down the peak, powerful winds turned difficult terrain treacherous.

Hours passed. We had no food or water. The trail was difficult. Our extra water we had stored under a tree was gone. It was getting late. Finally, we approached the trail head once again, and we felt completely defeated.

An avuncular old man ambled ahead of us. He was maybe 5 feet tall, completely bald, compensating with an enormous white beard.

To my surprise, it was an old Buddhist professor of mine from University. He was exploring the base of the mountain. His serenity was Yoda-like. He offered us jerky and water. “You look terrible! You really need electrolytes if you’re going to sweat all day,” he said.

The old man revived us even though we made mistakes, and his willingness to help was undeterred.

Truth, in the wilderness, is simple:

That helping one another is a wonderful obligation, and all lives are better for it.

Our public lands aren’t just an argument for the respect and love of nature. They are an argument for the respect and love of all people. Even Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot were explicit in the democratic and social aims of public lands.

Thanksgiving gives me a chance to reflect on the joy of America’s Greatest Idea, and the human legacy it carries on today.

Giving Thanks

This year, give thanks to the people and places that keep us sane.

Many hands make light work, on Borah or in Boise.

Reach out to your friends, meet new ones on the trail, or try to be one to yourself.

Happy Trails.

I do believe it is a decent bet that upon entering the wilderness a subtle and possibly unknowing deep humanity kicks in. I think that even the frenemies Muir and Pinchot would have had a delightful trip together on Borah or any other wild space that they found themselves. It did strike me though in your story that you may have paused for even a microsecond, when your stores were depleted and even before hand in the unfolding of the adventure, to recall your Eagle Board of Review and the standing query of the scout motto.

Well said. And I agree with that, BriKH: Should’ve been prepared!